June 24: 05F-8

For details on this sculpture, read the report integrated within this post after the images.

Improvising the Plan

"All God's critters got a voice in the choir

Some sing low and some sing higher

Some sing out loud on the telephone wire

Others clap their hands or paws or whatever they got."

"I don't know what happens. I'm a control freak, but when I get on the stage Trouble takes over. The audience throws me a word and she takes off."

It's hard for me to imagine her as a control freak. Her hands and face are active, involved, tracking what she's saying about her upcoming improv performance.

"That sounds a lot like sand sculpture. I come down here, make a pile and it's as if it's a surprise. 'Oh. I need to sculpt now.' Something does take over."

Except today. The sculpture plan bloomed in my mind, intact, the whole thing.

I have no words from an audience, but I do have memories. I pull one out and start carving. The sun has more patience than a club audience but is just as implacable. I pulled out an old fault--the leggy sculptures that show up now and then--and combined it with the current fascination with microfenestration. Pass all that by way of the D'ni Great Tree of Possibilities and you get... possibility. I could see the potential for production problems, but nothing gets creativity going like need.

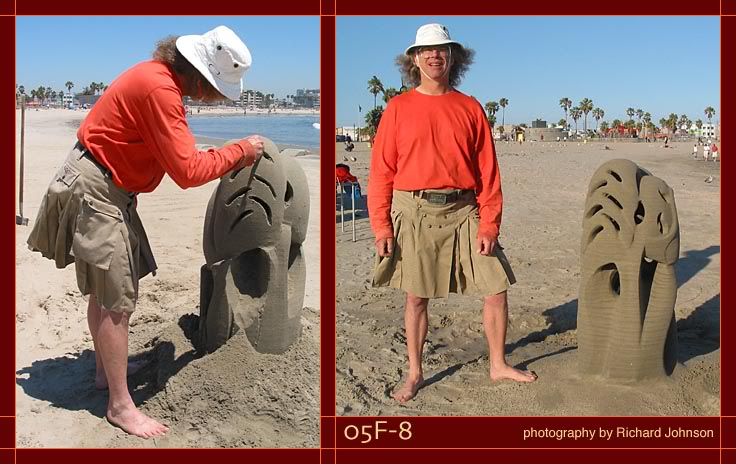

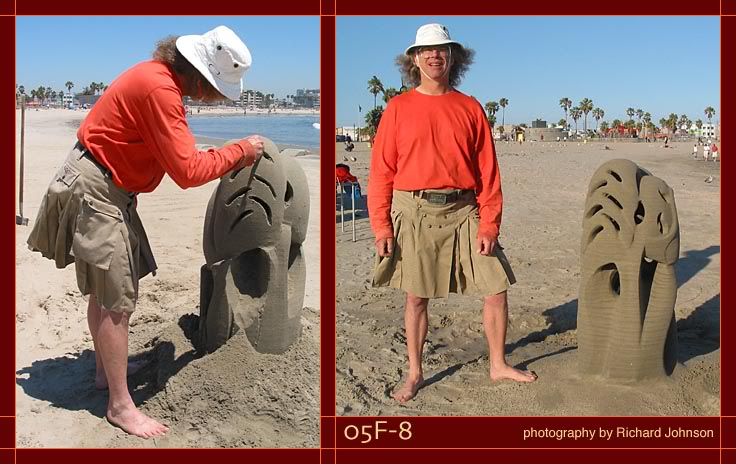

Build number: 05F-8 (lifetime start #306) filtered low tide sand

Title: "My Voice in the Choir"

Date: June 24 (Friday)

Location: Venice Breakwater, on the flat

Start: 0800; construction time approx 9,75 hours

Height: 3.4 feet (Latchform); sokkel height about 7 inches

Base: 1.75 feet nominal diameter

Assistant: none

Photo digital: EOS-1D walkaround and wide-angle details

Photo 35mm: none

Photo 6X7: none

Photo volunteer: Rich, with new A520 and my G2 (safety and builder)

Video: none

Equipment note: replacement sprayer gasket arrived Thursday

1. Expressing Love

It's a common comment, usually stated indirectly, but one person just came right out and said it. "I see love in the sculpture."

Where does love come from? What is it? It seems a concept highly resistant to rational consideration, needing a sort of surfer's feel of instantaneous response to the world. By the time I've done my usual consideration of things, any magic is pretty well gone. Perhaps sand sculpture is what flows slowly out of some porous layer in my soul, like water from years gone by out of an aquifer.

I'm content with leaving that particular sleeping dog alone. The pragmatist's major credo: "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Unfortunately for my on-board self confidence, God's way of working with souls doesn't include the ease and unchallenged comfort of His friends.

One night I got to thinking about God and love. I have become more porous to these ideas and the thoughts produced feelings... and no words. Jesus said "If you love me, do the things that I command you." He certainly didn't command sand sculpture.

Brennan Manning tells a story in "Ruthless Trust" (pardon quote inaccuracy here, I've given away all my copies of this) about a monk whose abilities were far beneath those of the other monks. He took to disappearing during the daily ceremonies and finally the leader found him, in the basement, dancing for God. Another monk was going to upbraid the little one, but the leader stopped him and said "Watch." The dancer finished his dance, and God showed his happiness.

Not everyone can be a solo singer. One time I was called up for jury duty and one of the questions asked of prospective jurors was "Do you consider yourself a leader or a follower?" Every one of them responded with "Leader."

You can either complain about getting lemons, or go make lemonade. I prefer cooking to complaining. Who am I to tell God that he can't invite a sand sculptor to work with him? There are messages overt and covert, and just about everyone is tired of the overt kind. Sand sculpture is what it is. If people see love, so be it.

2. Technical Problems

One can do sand sculpture with nothing more than hands. A mussel shell is optional, but nice. I do this kind of sculpture as a reminder, and because it's a pure expression of spontaneous design.

There's a middle ground of equipment and technique. The idea here is production. Big sculptures, big piles, fast work that doesn't involve the interior.

At the other extreme is my equipment-dependent perfectionist approach. When my sprayer broke during the execution of last week's sculpture it became a race between dehydration and completion. Completion won, barely. A few minutes later a friend came by and found part of the sculpture on the ground. I sent a rather peeved Email to the company and their response was gracious. The new gasket arrived in time to enable the sculpture plan.

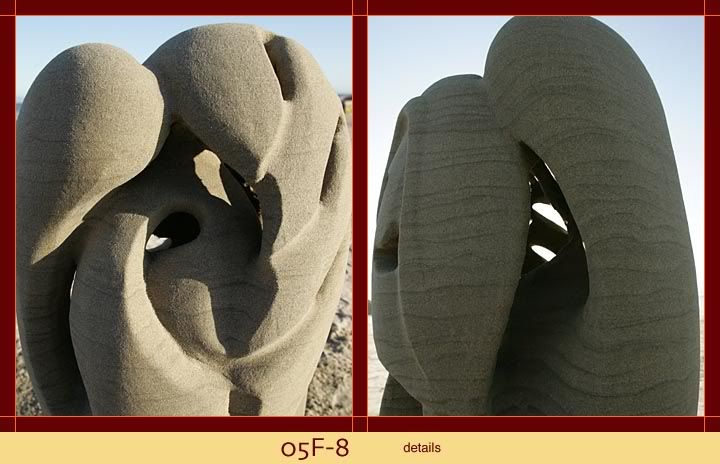

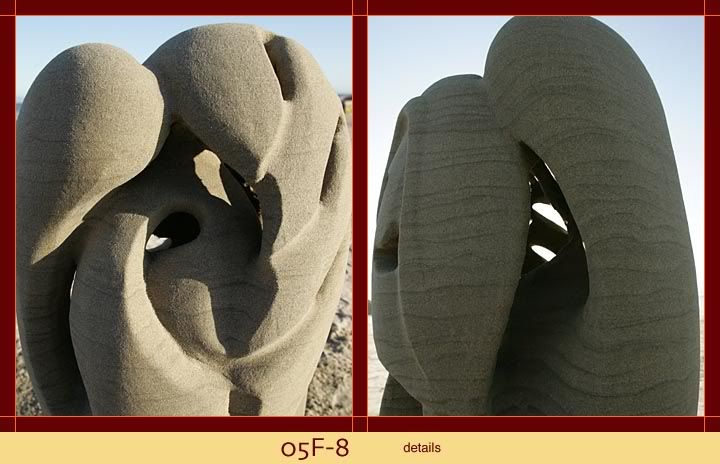

The rest of it was smooth, until it came time to carve. The sculpture's idea centered on a tree of rounded shapes, hollow and windowed, supported by limbs and trunks. The whole thing depended on being able to hollow the rounded forms at the top but the plan allowed none of the big openings I usually have for tool access. My tools are far beyond the basic mussel shell but that engenders confidence that has been pushing me ever farther into interior carving.

"I know what I need to do, Rich, but how am I going to do it?" I sit on the sand, looking at the sculpture-in-process, and nearly despair.

"Radar guidance? Prehensile tools? Hinges?"

The answer turns out to be a combination of every trick I've ever learned about carving, and then improvising on them. I peer through little holes at a tool that's held in a hand deep inside the sculpture, arm through an opening barely big enough to admit it. Most of the carving goes by feel and sound. I can hear the tool cut and as the tone changes I know the surface is getting thinner. I have to visualize where the parts meet so as to leave enough meat to hold them up.

3. Design

Think of an abstraction a tree, a child's version. A trunk, some limbs and then balls of undifferentiated leaves. Cut off the top part and you have the plan. Of course, this tree will be turned inward due to engineering necessity, but the rounded forms will be good canvases for microsculpture.

"What is it?"

"It's abstract. Whatever you see in it." The sculpture is pretty well roughed out, with some hollows started.

"I see a tree."

I turn and look at her. "How about that, Rich. She got it in one guess. By the way, I'm not going for the Johnson Abstract Prize today."

"That's good, because you have Snoopy there on the side."

"Where?"

"You just put in his nose."

"I see. Has an awfully tall forehead, don't you think? Don't worry. I'll de-Snoopy it in a little bit."

"That's fine. As long as you don't make another 'Palomar.'"

Rich has a long memory. That 1996 sculpture was memorable for all the wrong reasons. It was an early attempt at a semi-representational sculpture inspired by reading a book about the construction of the Palomar observatory. It stood but was still a failure, classed as one of the all-time stinkers I've made. I have improved in my ability to build models in my mind, and in my ability to carve. Today is the first time since 2003 that I've tried to hew to a fairly tight plan, and it's looking a lot better than "Palomar."

The tree shapes remind me of Disney's idealized ones from "Fantasia." The thought produces some discomfort, but that movie still resonates in me. I see other things from it all the time; all the foliage in the Nutcracker Suite section was taken from California chaparral.

When the tree-tops are close to their final shape I have to get serious about hollowing them out. This proves to be impossible with current tools and sculpture design. No thin sections this time, which is a big problem. Every pound of sand up on top requires more everywhere, all the way to the ground to hold it up. If I could start with thin legs I could get inside to hollow out the top but the whole thing would fall.

Then I remember a trick from the early days of microsculpture: thin it out after carving the small windows. Angled tools make this possible. I carve out as much as I can from the inside, then cut the slots. A combination of reaching around corners, cutting at an angle from the outside and using small curved tools produces something close to the thin sections I want. The top parts, envisioned as airy and light, are still too heavy, so the limbs will have to be thicker.

There are four major areas I've intended to carve into the interlaced slots that I hoped would suggest branches. I do the first and then contemplate the rest. Anyone who knows me will tell you I have a problem with discipline and the thought of doing the same thing three more times is intolerable.

"Every sculptor has the right to be silly once, Rich."

"How so?"

"I want a curlicue. Right here." I use the tent stake to bore the initial hole, then carve the whole thing into a sort of large pug's tail. It has nothing to do with the original plan but it does fit very well with rest, especially after some detail work on the overlapping edge to the west.

Around the sculpture is another blank panel. Taking off from a leaf-shaped window between convex panels, I sketch in a vine and then carve away either side of it, so the vine stem is raised.

"If you can't thin it from the inside, do so from the outside, right?"

"Sounds good to me."

As long as it involves more holes, Rich agrees with what I do. In this case, the raised vine is accompanied by leaf-shaped holes that follow it across the broad panel.

"I need another leaf there, but this wasn't in the plan and I need that sand to hold up the other stuff."

"Good idea."

As the day progresses the piece takes on nice shadows. The vine works well with its neighboring elements, even if it isn't terrific by itself. Three down, one to go.

"The more I look at this part, Rich, the more I'm tempted to leave it alone. It's a nice shape, and I like the way the light outlines the top. Anything else might be too much."

"You do have some work to do on the bottom."

"You're right."

In the end, it works. Partly. Viewed from the southwest in the late afternoon light the tree motif is obvious, and beautiful, even with the vine diversion on top. Elsewhere the accidents aren't so happy, and one major failing is the lack of differentiation of limbs and "foliage." I simply forgot to undercut the edges where the tree tops join the limbs to show the separation.

I work my way around the sculpture, spiralling downward from top to bottom, cleaning it up.

"This one really responds well to clean-up," Rich observes."

"I've been disappointed with the last few. They were pretty sloppy." One thing I did differently here was to bring individual elements closer to completion so that later clean-up wouldn't be quite so much of a chore.

Finally, it's done. I make the signature pad and sign it. I'm amazed it's still here. God's being nice to me. This thing should explode; where's the support? The Holy Spirit holds it together as He holds me.

3. Feeling

Sculptures used to have magic. In 1984 every one was magic. I didn't know where they came from and the shapes were straight from somewhere I didn't want to know very well for fear of killing it off. What I understand I usually file away and forget.

The sculpture process still fascinates me but has become as routine as improvisational design can be. I have confidence that if I'm faced with a block of uncarved sand I'll be able to make something that looks good out of it. It'll be an engineering challenge, an intellectual design challenge, but sometimes I think the heart has been buried or forgotten.

God wants me to know what I'm doing. He wants me to be able to love, and know I'm loving. Rather that distancing myself intellectually from everything, he wants me right there, in the moment, with Him and with others. And my sculptures.

This one is here. It rings, and the ringing resonates in me. I'm not sure what it is. Maybe it's the metaphor-trees, a cultural engram by way of DNA and Disney. Maybe it's the rounded shapes so eloquent of biology. Common memory, an archetype, something that connects to deep preferences and desires.

As I talk with the improv performer her enthusiasm rubs off onto me. Good sculptures charge me up even if my brain is gone. Maybe it's enthusiasm, God's and mine, that's holding this impossible sculpture together.

I'm delighted that I made it. Faults and all, it's quite a piece. I stay up half the night on Until Uru, babbling my head off about it and other things. The people there are beginning to understand Post-Sculptural Syndrome.

Written 2005 June 25

"All God's Critters" by Bill Staines, sung by John McCutcheon on "Howjadoo"

Improvising the Plan

"All God's critters got a voice in the choir

Some sing low and some sing higher

Some sing out loud on the telephone wire

Others clap their hands or paws or whatever they got."

"I don't know what happens. I'm a control freak, but when I get on the stage Trouble takes over. The audience throws me a word and she takes off."

It's hard for me to imagine her as a control freak. Her hands and face are active, involved, tracking what she's saying about her upcoming improv performance.

"That sounds a lot like sand sculpture. I come down here, make a pile and it's as if it's a surprise. 'Oh. I need to sculpt now.' Something does take over."

Except today. The sculpture plan bloomed in my mind, intact, the whole thing.

I have no words from an audience, but I do have memories. I pull one out and start carving. The sun has more patience than a club audience but is just as implacable. I pulled out an old fault--the leggy sculptures that show up now and then--and combined it with the current fascination with microfenestration. Pass all that by way of the D'ni Great Tree of Possibilities and you get... possibility. I could see the potential for production problems, but nothing gets creativity going like need.

Build number: 05F-8 (lifetime start #306) filtered low tide sand

Title: "My Voice in the Choir"

Date: June 24 (Friday)

Location: Venice Breakwater, on the flat

Start: 0800; construction time approx 9,75 hours

Height: 3.4 feet (Latchform); sokkel height about 7 inches

Base: 1.75 feet nominal diameter

Assistant: none

Photo digital: EOS-1D walkaround and wide-angle details

Photo 35mm: none

Photo 6X7: none

Photo volunteer: Rich, with new A520 and my G2 (safety and builder)

Video: none

Equipment note: replacement sprayer gasket arrived Thursday

1. Expressing Love

It's a common comment, usually stated indirectly, but one person just came right out and said it. "I see love in the sculpture."

Where does love come from? What is it? It seems a concept highly resistant to rational consideration, needing a sort of surfer's feel of instantaneous response to the world. By the time I've done my usual consideration of things, any magic is pretty well gone. Perhaps sand sculpture is what flows slowly out of some porous layer in my soul, like water from years gone by out of an aquifer.

I'm content with leaving that particular sleeping dog alone. The pragmatist's major credo: "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Unfortunately for my on-board self confidence, God's way of working with souls doesn't include the ease and unchallenged comfort of His friends.

One night I got to thinking about God and love. I have become more porous to these ideas and the thoughts produced feelings... and no words. Jesus said "If you love me, do the things that I command you." He certainly didn't command sand sculpture.

Brennan Manning tells a story in "Ruthless Trust" (pardon quote inaccuracy here, I've given away all my copies of this) about a monk whose abilities were far beneath those of the other monks. He took to disappearing during the daily ceremonies and finally the leader found him, in the basement, dancing for God. Another monk was going to upbraid the little one, but the leader stopped him and said "Watch." The dancer finished his dance, and God showed his happiness.

Not everyone can be a solo singer. One time I was called up for jury duty and one of the questions asked of prospective jurors was "Do you consider yourself a leader or a follower?" Every one of them responded with "Leader."

You can either complain about getting lemons, or go make lemonade. I prefer cooking to complaining. Who am I to tell God that he can't invite a sand sculptor to work with him? There are messages overt and covert, and just about everyone is tired of the overt kind. Sand sculpture is what it is. If people see love, so be it.

2. Technical Problems

One can do sand sculpture with nothing more than hands. A mussel shell is optional, but nice. I do this kind of sculpture as a reminder, and because it's a pure expression of spontaneous design.

There's a middle ground of equipment and technique. The idea here is production. Big sculptures, big piles, fast work that doesn't involve the interior.

At the other extreme is my equipment-dependent perfectionist approach. When my sprayer broke during the execution of last week's sculpture it became a race between dehydration and completion. Completion won, barely. A few minutes later a friend came by and found part of the sculpture on the ground. I sent a rather peeved Email to the company and their response was gracious. The new gasket arrived in time to enable the sculpture plan.

The rest of it was smooth, until it came time to carve. The sculpture's idea centered on a tree of rounded shapes, hollow and windowed, supported by limbs and trunks. The whole thing depended on being able to hollow the rounded forms at the top but the plan allowed none of the big openings I usually have for tool access. My tools are far beyond the basic mussel shell but that engenders confidence that has been pushing me ever farther into interior carving.

"I know what I need to do, Rich, but how am I going to do it?" I sit on the sand, looking at the sculpture-in-process, and nearly despair.

"Radar guidance? Prehensile tools? Hinges?"

The answer turns out to be a combination of every trick I've ever learned about carving, and then improvising on them. I peer through little holes at a tool that's held in a hand deep inside the sculpture, arm through an opening barely big enough to admit it. Most of the carving goes by feel and sound. I can hear the tool cut and as the tone changes I know the surface is getting thinner. I have to visualize where the parts meet so as to leave enough meat to hold them up.

3. Design

Think of an abstraction a tree, a child's version. A trunk, some limbs and then balls of undifferentiated leaves. Cut off the top part and you have the plan. Of course, this tree will be turned inward due to engineering necessity, but the rounded forms will be good canvases for microsculpture.

"What is it?"

"It's abstract. Whatever you see in it." The sculpture is pretty well roughed out, with some hollows started.

"I see a tree."

I turn and look at her. "How about that, Rich. She got it in one guess. By the way, I'm not going for the Johnson Abstract Prize today."

"That's good, because you have Snoopy there on the side."

"Where?"

"You just put in his nose."

"I see. Has an awfully tall forehead, don't you think? Don't worry. I'll de-Snoopy it in a little bit."

"That's fine. As long as you don't make another 'Palomar.'"

Rich has a long memory. That 1996 sculpture was memorable for all the wrong reasons. It was an early attempt at a semi-representational sculpture inspired by reading a book about the construction of the Palomar observatory. It stood but was still a failure, classed as one of the all-time stinkers I've made. I have improved in my ability to build models in my mind, and in my ability to carve. Today is the first time since 2003 that I've tried to hew to a fairly tight plan, and it's looking a lot better than "Palomar."

The tree shapes remind me of Disney's idealized ones from "Fantasia." The thought produces some discomfort, but that movie still resonates in me. I see other things from it all the time; all the foliage in the Nutcracker Suite section was taken from California chaparral.

When the tree-tops are close to their final shape I have to get serious about hollowing them out. This proves to be impossible with current tools and sculpture design. No thin sections this time, which is a big problem. Every pound of sand up on top requires more everywhere, all the way to the ground to hold it up. If I could start with thin legs I could get inside to hollow out the top but the whole thing would fall.

Then I remember a trick from the early days of microsculpture: thin it out after carving the small windows. Angled tools make this possible. I carve out as much as I can from the inside, then cut the slots. A combination of reaching around corners, cutting at an angle from the outside and using small curved tools produces something close to the thin sections I want. The top parts, envisioned as airy and light, are still too heavy, so the limbs will have to be thicker.

There are four major areas I've intended to carve into the interlaced slots that I hoped would suggest branches. I do the first and then contemplate the rest. Anyone who knows me will tell you I have a problem with discipline and the thought of doing the same thing three more times is intolerable.

"Every sculptor has the right to be silly once, Rich."

"How so?"

"I want a curlicue. Right here." I use the tent stake to bore the initial hole, then carve the whole thing into a sort of large pug's tail. It has nothing to do with the original plan but it does fit very well with rest, especially after some detail work on the overlapping edge to the west.

Around the sculpture is another blank panel. Taking off from a leaf-shaped window between convex panels, I sketch in a vine and then carve away either side of it, so the vine stem is raised.

"If you can't thin it from the inside, do so from the outside, right?"

"Sounds good to me."

As long as it involves more holes, Rich agrees with what I do. In this case, the raised vine is accompanied by leaf-shaped holes that follow it across the broad panel.

"I need another leaf there, but this wasn't in the plan and I need that sand to hold up the other stuff."

"Good idea."

As the day progresses the piece takes on nice shadows. The vine works well with its neighboring elements, even if it isn't terrific by itself. Three down, one to go.

"The more I look at this part, Rich, the more I'm tempted to leave it alone. It's a nice shape, and I like the way the light outlines the top. Anything else might be too much."

"You do have some work to do on the bottom."

"You're right."

In the end, it works. Partly. Viewed from the southwest in the late afternoon light the tree motif is obvious, and beautiful, even with the vine diversion on top. Elsewhere the accidents aren't so happy, and one major failing is the lack of differentiation of limbs and "foliage." I simply forgot to undercut the edges where the tree tops join the limbs to show the separation.

I work my way around the sculpture, spiralling downward from top to bottom, cleaning it up.

"This one really responds well to clean-up," Rich observes."

"I've been disappointed with the last few. They were pretty sloppy." One thing I did differently here was to bring individual elements closer to completion so that later clean-up wouldn't be quite so much of a chore.

Finally, it's done. I make the signature pad and sign it. I'm amazed it's still here. God's being nice to me. This thing should explode; where's the support? The Holy Spirit holds it together as He holds me.

3. Feeling

Sculptures used to have magic. In 1984 every one was magic. I didn't know where they came from and the shapes were straight from somewhere I didn't want to know very well for fear of killing it off. What I understand I usually file away and forget.

The sculpture process still fascinates me but has become as routine as improvisational design can be. I have confidence that if I'm faced with a block of uncarved sand I'll be able to make something that looks good out of it. It'll be an engineering challenge, an intellectual design challenge, but sometimes I think the heart has been buried or forgotten.

God wants me to know what I'm doing. He wants me to be able to love, and know I'm loving. Rather that distancing myself intellectually from everything, he wants me right there, in the moment, with Him and with others. And my sculptures.

This one is here. It rings, and the ringing resonates in me. I'm not sure what it is. Maybe it's the metaphor-trees, a cultural engram by way of DNA and Disney. Maybe it's the rounded shapes so eloquent of biology. Common memory, an archetype, something that connects to deep preferences and desires.

As I talk with the improv performer her enthusiasm rubs off onto me. Good sculptures charge me up even if my brain is gone. Maybe it's enthusiasm, God's and mine, that's holding this impossible sculpture together.

I'm delighted that I made it. Faults and all, it's quite a piece. I stay up half the night on Until Uru, babbling my head off about it and other things. The people there are beginning to understand Post-Sculptural Syndrome.

Written 2005 June 25

"All God's Critters" by Bill Staines, sung by John McCutcheon on "Howjadoo"